Essays: PAHSA Cambodia Short Program II

The Second PAHSA Cambodia Short Study Program took place from 13-24 September 2015 at Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC). The focus of the program was poverty alleviation. Students were offered a unique opportunity to learn comprehensively about some of the critical issues that affect peace and human security in Cambodia and its neighboring areas, there was a particular focus on poverty alleviation. Ten students from the PAHSA Japanese university consortium partners attended the program.

Phnom Penh: Broadening Our Vision

OSIPP, Osaka University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

I was very lucky to travel to Cambodia and take part in the PAHSA program from 13 to 23 September 2015. The program passed like a whirlwind and we all experienced so much although it was very short time.

There were eight lectures during the program and these covered topics ranging from economic development, poverty alleviation, to women’s peace and security. The students participating on the program, all from the PAHSA Japanese consortium partner universities, came from different academic backgrounds, and this fact, together with the diverse range of lectures, helped to broaden all of our visions massively.

Besides the excellent lectures, we also had three visits to places outside the university. These included an NGO working with children, Cambodia’s Ministry of Justice, and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. These visits helped put into context some of the lecture content from the classroom. It also made everything more tangible; we had the opportunity to taste the real Cambodia first hand.

In addition to lectures and trips, we also had informal discussions during the program. These sessions offered the chance to exchange personal views in a more informal setting. This was enlightening especially during the roundtable discussions with PUC students and these helped to further our understanding of Cambodian history and contemporary society as well as the PUC students’ understanding of Japan and it’s responsibilities.

In our free time, PUC students kindly took us sightseeing around Phnom Penh. As strange as it seems, although we spent a limited together, bonds formed quickly and we became good friends.

As the program wound down, participants from the Japanese side made presentations on the last day about what we had learned and thought during our time in Cambodia. Each of us picked different topics and all gave 100 percent.

Ms. Kajita from Osaka University talked about the legal and judicial reform in Cambodia; and I shared opinions on the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations in Cambodia with other students; Mr. Shiroma, from Meio University, presented on the theme of development with peace, and since he is from Okinawa, also talked about the Cambodia-Okinawa ‘Peace Museum’ Cooperation Project; Mr. Tengku, from Osaka University, offered analysis on development strategy for poverty in Cambodia using the SWOT method; Ms. Horiguchi, a student from Osaka University, talked about migrant workers in Cambodia; Ms. Iwane, from Osaka University too, made a presentation on reconciliation and peacebuilding, she also connected the case of Cambodia with her own research; Ms. Oyama, from Hiroshima University, an expert on education, shared some of her Cambodian field work; and finally, Ms. Adriana, also from Hiroshima University, talked about the importance of peace education.

Closing out the formal part of the program, Prof. Trond and Prof. Matsuno summed things up on a positive note and everyone received ASAD hats.

In the 2015 fall semester, two students from PUC will study at Osaka University and I will be fortunate to have a chance to participate in their classes, too.

As I close this this report, I would like to steal a line from Ms. Adriana’s presentation where she quoted from the Dalai Lama: “When educating the minds of youth, we must not forget to educate their hearts.”

I’m sure I speak for us all when I say the PAHSA short program in Cambodia touched our minds and hearts. I’m certain that we’re all more resourceful students and better researchers than we were before. Thank you PAHSA.

There were eight lectures during the program and these covered topics ranging from economic development, poverty alleviation, to women’s peace and security. The students participating on the program, all from the PAHSA Japanese consortium partner universities, came from different academic backgrounds, and this fact, together with the diverse range of lectures, helped to broaden all of our visions massively.

Besides the excellent lectures, we also had three visits to places outside the university. These included an NGO working with children, Cambodia’s Ministry of Justice, and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. These visits helped put into context some of the lecture content from the classroom. It also made everything more tangible; we had the opportunity to taste the real Cambodia first hand.

In addition to lectures and trips, we also had informal discussions during the program. These sessions offered the chance to exchange personal views in a more informal setting. This was enlightening especially during the roundtable discussions with PUC students and these helped to further our understanding of Cambodian history and contemporary society as well as the PUC students’ understanding of Japan and it’s responsibilities.

In our free time, PUC students kindly took us sightseeing around Phnom Penh. As strange as it seems, although we spent a limited together, bonds formed quickly and we became good friends.

As the program wound down, participants from the Japanese side made presentations on the last day about what we had learned and thought during our time in Cambodia. Each of us picked different topics and all gave 100 percent.

Ms. Kajita from Osaka University talked about the legal and judicial reform in Cambodia; and I shared opinions on the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations in Cambodia with other students; Mr. Shiroma, from Meio University, presented on the theme of development with peace, and since he is from Okinawa, also talked about the Cambodia-Okinawa ‘Peace Museum’ Cooperation Project; Mr. Tengku, from Osaka University, offered analysis on development strategy for poverty in Cambodia using the SWOT method; Ms. Horiguchi, a student from Osaka University, talked about migrant workers in Cambodia; Ms. Iwane, from Osaka University too, made a presentation on reconciliation and peacebuilding, she also connected the case of Cambodia with her own research; Ms. Oyama, from Hiroshima University, an expert on education, shared some of her Cambodian field work; and finally, Ms. Adriana, also from Hiroshima University, talked about the importance of peace education.

Closing out the formal part of the program, Prof. Trond and Prof. Matsuno summed things up on a positive note and everyone received ASAD hats.

In the 2015 fall semester, two students from PUC will study at Osaka University and I will be fortunate to have a chance to participate in their classes, too.

As I close this this report, I would like to steal a line from Ms. Adriana’s presentation where she quoted from the Dalai Lama: “When educating the minds of youth, we must not forget to educate their hearts.”

I’m sure I speak for us all when I say the PAHSA short program in Cambodia touched our minds and hearts. I’m certain that we’re all more resourceful students and better researchers than we were before. Thank you PAHSA.

Serious faces on the first morning of the first day of the PAHSA Second Short Program in Cambodia

Stark Differences to Japan

OSIPP, Osaka University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

From 13 to 23 of September, along with a group of students from Japan, I went to Pannasastra University of Cambodia to study Peace and Human Security with a focus on poverty alleviation. It was a great chance to study this topic alongside Cambodian students. There were lectures, field trips, and informal tutorial sessions as the program progressed. We had a chance to visit an orphanage, the Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate, the Ministry of Justice, the JICA Cambodia office, and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Although we all had many interesting experiences on the program, I would like to just focus on the most memorable.

The visit to Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum was haunting. In its origin, the museum was a high school, but during the Pol Pot era, the place of learning became a notorious prison known as S21, the largest in Cambodia. From 1975 to 1978, it is reported that more than 17,000 people were killed there. The building is preserved so visitors can properly feel its horrors, the story it has to tell. The torture and killings that took place were photographically documented and these images adorn the walls. Words cannot express what can be seen in the eyes and hollow faces of the torture victims.

Even though some time has passed since we visited the museum, it is still difficult to put into words my feeling about this place. I took some photos during the visit but I have not wished to look at them. The only thing that I can say is the experience of Tuol Sleng Gencide Museum will stay with me a lifetime.

More positively however, the orphanage that we visited during the program was memorable too. While there I was surprised to hear orphanage staff say that those children were the lucky ones. There are many other impoverished children who survive hand-to-mouth in Cambodia without shelter. The difference to Japan is stark. The Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate houses around 300 orphans, I have never heard of such a large facility in Japan. With a history of civil conflict and war, many Cambodians suffered great psychological damage and family rehabilitation is sometimes desperate. This is one reason for the legions of needy children in Cambodia.

In Cambodia, the huge gap between the rich and the poor is vast. Luxury shopping malls sit cheek-by-jowl with slums and wretched poverty. Yet on entering the Aeon mall, the experience is the same as its namesake in Japan. Ticket prices are also similar, and of course, prohibitively expensive for the majority of Cambodia’s citizens. But unlike Japan, just outside the mall and around the tourist spots, scores of beggars jostle to catch the eye of tourists. For me, it was first time seeing child beggars hammering on car windows at traffic lights. I could do nothing for them and feelings of hopelessness washed over me.

Overall, the PAHSA short program in Cambodia was enlightening. I experienced many new things, experiences that could only be of benefit as a student of International Public Policy.

The visit to Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum was haunting. In its origin, the museum was a high school, but during the Pol Pot era, the place of learning became a notorious prison known as S21, the largest in Cambodia. From 1975 to 1978, it is reported that more than 17,000 people were killed there. The building is preserved so visitors can properly feel its horrors, the story it has to tell. The torture and killings that took place were photographically documented and these images adorn the walls. Words cannot express what can be seen in the eyes and hollow faces of the torture victims.

Even though some time has passed since we visited the museum, it is still difficult to put into words my feeling about this place. I took some photos during the visit but I have not wished to look at them. The only thing that I can say is the experience of Tuol Sleng Gencide Museum will stay with me a lifetime.

More positively however, the orphanage that we visited during the program was memorable too. While there I was surprised to hear orphanage staff say that those children were the lucky ones. There are many other impoverished children who survive hand-to-mouth in Cambodia without shelter. The difference to Japan is stark. The Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate houses around 300 orphans, I have never heard of such a large facility in Japan. With a history of civil conflict and war, many Cambodians suffered great psychological damage and family rehabilitation is sometimes desperate. This is one reason for the legions of needy children in Cambodia.

In Cambodia, the huge gap between the rich and the poor is vast. Luxury shopping malls sit cheek-by-jowl with slums and wretched poverty. Yet on entering the Aeon mall, the experience is the same as its namesake in Japan. Ticket prices are also similar, and of course, prohibitively expensive for the majority of Cambodia’s citizens. But unlike Japan, just outside the mall and around the tourist spots, scores of beggars jostle to catch the eye of tourists. For me, it was first time seeing child beggars hammering on car windows at traffic lights. I could do nothing for them and feelings of hopelessness washed over me.

Overall, the PAHSA short program in Cambodia was enlightening. I experienced many new things, experiences that could only be of benefit as a student of International Public Policy.

“The lucky ones.” Mealtime for hundreds of orphans at The Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate.

Tapping Youth Potential

IDEC, Hiroshima University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

The PAHSA exchange program in Cambodia was an excellent opportunity for students to learn more regarding Poverty alleviation, peacebuilding, conflict resolution and gender equality. All of those elements put into the context of Cambodia’s plan of development were extremely interesting and provided a ‘new light’ of knowledge for my personal research (demography issues in Poland and Japan). The Cambodia case was quite interesting, so I decided to do a little bit more research regarding its population and use the information obtained through the program to examine it a little further.

Cambodia has one of the youngest populations in the world. According to estimates provided by international agencies (CIA Factbook 2014) approximately 51% (0-14 years: 31.43%, 15-24 years: 19.71%) of the overall population is below 25 years old. The total population is 15,7 million people, more than 8 million is regarded as young and the average age is 25 years old.

This issue was brought about by the disturbance in the flow of population growth by the Pol Pot regime and the Khmer Rouge reign of terror. From 1975 to 1979, when Pol Pot’s revolutionary army captured the capital Phnom Penh, he began an ethnic cleansing of his own citizens and so called enemies of the state. Today it is known as one of the most barbarous genocides in the history of humankind. During his reign more than 25% of the population of Cambodia was killed or went ‘missing.’ Routine torture, work camp conditions, selective mass killings, starvation, and the lack of basic health care all took a massive toll.

By visiting the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Phen we were able to grasp the reality of this monstrosity. The use of children as judges to decide who should live and die was extremely deviant. Pol Pot regarded children as pure and innocent and that is why they were responsible for death or torture verdicts. The deprived mechanisms used by the military to deal with the enemies of the Khmer Rogue regime were malicious.

The sudden decrease of the population had negative consequences in the overall well-being of the people (divided families, orphans) which caused several problems, including the immediate impoverishment, lack of basic needs, fresh water, food and shelter.

When the regime was forced from power the situation did not soon improve. Only with the intervention of the United Nations and their mission in 1992-93 and the possibility of aid from other countries emerged. Pol Pot’s genocide caused a large gap within the population growth, which is why today many families possess large numbers of offspring to insure security and a stable life for the passing generation. But it also caused additional problems of children without families or left in situations in which they were abandoned after birth. In Cambodia there is an extremely strong notion of this issue.

By visiting local NGO’s we were able to observe one of the most successful orphanages in Phnom Penh. We were surprised to see that it is more of a complex of buildings all with different functions. The orphanage, called Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate (FLOW) takes care of hundreds of children. FLOW does not only help them to survive day-to-day, but also takes care of their future needs and helps them to become fully-fledged citizens. Those daily activities are: computer classes, English classes, and several cultural activities. The timetable helps to create a steady rhythm of the day for the children and prepare them to become responsible citizens.

The son of the founder of FLOW was happy to share with us that most of the orphans that became adults obtained good jobs and were able to create their own families and live normal lives. But he stated that there were still too many children without help and that the orphanage can only assist the desperate few. The number of children that are in need help is impossible to determine because of the lack accurate census data. The last census in Cambodia (2013) was only possible with the assistance of the Japanese government.

Cambodia is one of the developing countries in South-East Asia that would like to walk the same path as successful ‘Asian Tigers,’ but with extremely low interest from international capital and with current social-economic problems, it seems a tall order. However the young generation shows tremendous potential with their skills and knowledge, and they may well be the saviors for this country. If this potential is not tapped, there could be a brain drain. It would be sad if the potential of Cambodia’s young went to benefit neighboring countries.

Cambodia has one of the youngest populations in the world. According to estimates provided by international agencies (CIA Factbook 2014) approximately 51% (0-14 years: 31.43%, 15-24 years: 19.71%) of the overall population is below 25 years old. The total population is 15,7 million people, more than 8 million is regarded as young and the average age is 25 years old.

This issue was brought about by the disturbance in the flow of population growth by the Pol Pot regime and the Khmer Rouge reign of terror. From 1975 to 1979, when Pol Pot’s revolutionary army captured the capital Phnom Penh, he began an ethnic cleansing of his own citizens and so called enemies of the state. Today it is known as one of the most barbarous genocides in the history of humankind. During his reign more than 25% of the population of Cambodia was killed or went ‘missing.’ Routine torture, work camp conditions, selective mass killings, starvation, and the lack of basic health care all took a massive toll.

By visiting the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Phen we were able to grasp the reality of this monstrosity. The use of children as judges to decide who should live and die was extremely deviant. Pol Pot regarded children as pure and innocent and that is why they were responsible for death or torture verdicts. The deprived mechanisms used by the military to deal with the enemies of the Khmer Rogue regime were malicious.

The sudden decrease of the population had negative consequences in the overall well-being of the people (divided families, orphans) which caused several problems, including the immediate impoverishment, lack of basic needs, fresh water, food and shelter.

When the regime was forced from power the situation did not soon improve. Only with the intervention of the United Nations and their mission in 1992-93 and the possibility of aid from other countries emerged. Pol Pot’s genocide caused a large gap within the population growth, which is why today many families possess large numbers of offspring to insure security and a stable life for the passing generation. But it also caused additional problems of children without families or left in situations in which they were abandoned after birth. In Cambodia there is an extremely strong notion of this issue.

By visiting local NGO’s we were able to observe one of the most successful orphanages in Phnom Penh. We were surprised to see that it is more of a complex of buildings all with different functions. The orphanage, called Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate (FLOW) takes care of hundreds of children. FLOW does not only help them to survive day-to-day, but also takes care of their future needs and helps them to become fully-fledged citizens. Those daily activities are: computer classes, English classes, and several cultural activities. The timetable helps to create a steady rhythm of the day for the children and prepare them to become responsible citizens.

The son of the founder of FLOW was happy to share with us that most of the orphans that became adults obtained good jobs and were able to create their own families and live normal lives. But he stated that there were still too many children without help and that the orphanage can only assist the desperate few. The number of children that are in need help is impossible to determine because of the lack accurate census data. The last census in Cambodia (2013) was only possible with the assistance of the Japanese government.

Cambodia is one of the developing countries in South-East Asia that would like to walk the same path as successful ‘Asian Tigers,’ but with extremely low interest from international capital and with current social-economic problems, it seems a tall order. However the young generation shows tremendous potential with their skills and knowledge, and they may well be the saviors for this country. If this potential is not tapped, there could be a brain drain. It would be sad if the potential of Cambodia’s young went to benefit neighboring countries.

The skills and knowledge of the young generation offers hope for Cambodia.

Positive and Negative Peace

Meio University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

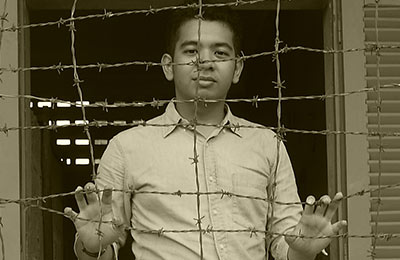

We could see crude beds, cells, gallows, clothes, human skulls and photos of victims everywhere. They were just real, gloomy; it was the atmosphere of genocide. Prisoners at S-21 (Security Office 21) were strictly regulated: ‘Do nothing; sit still and wait for my orders; if there is no order, keep quiet; When asked to do something, you must do it right away without protesting.’ It is estimated that 14,000 to 20,000 prisoners perished while held there, only eight survived.

In the Building B of what the now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, I noticed an exhibition introducing current museum activities. There was an exhibition about a Cambodia/Okinawa collaboration project which peaked my interest. It is a program where Okinawa and Cambodia, each having shared war experience on their soil, worked together to create museums that would generate a ‘peace culture’ based on the painful lessons learnt from their past. Through the project, seven members of the museum staff were trained for a month in Okinawa in all aspects of museum management. After returning to Cambodia, they utilized their training efforts in drafting action plans for the long-term management of Cambodia’s museum artifacts. The project started in 2012 and concluded in 2014. Although I live in Okinawa, I had no idea about this initiative and it and came as a surprise because I never expected that Cambodia would have a connection with my home.

During the program I learnt about two distinctive perspectives on peace that I hadn’t considered before. One is ‘negative peace’ that is the absence of war or armed conflict. The other one is ‘positive peace’ that is the presence of social justice and equality, and the absence of structural or indirect violence. For Cambodia, given its turbulent history, the country has been on the track of improvement in recent years. It is obviously peaceful when compared to the past, but still there are many obstacles such as hunger, levels of education, public health, gender equality, child mortality and so on. There is no war now but other threats still remain for the people of Cambodia.

Cambodia’s educational system offers examples of some of the issues that are yet to be resolved as the country develops. The Education network was torn apart during the Khmer Rouge regime, and when order returned, the education system was reconstructed from almost nothing in the 1980s and 90s. But there is still much to do. Although primary school enrolment is around 90%, the dropout rate is high. Half of the students who enter primary school fail to finish. Financial challenges and the need to become breadwinners lead to dwindling student enrolment, and when this takes place the opportunity to learn precious life skills passes by. Apart from on the academic side, missing school can also lead to poor social skills and a lack of responsibility in the young. As a result, some of Cambodia’s youths have poor communication skills, develop bad attitudes, and experience a loss of spiritual development.

My time in Cambodia has focused my attention on peace, the ‘real’ meaning of peace, and ‘effective’ peace education. It also pushed me to think more about my own attitudes, my education in Okinawa, and an individual’s personal responsibilities. Although it was unexpected when I arrived in Cambodia, the PASHA short program left me thinking as much about peace as an Okinawan, for my home prefecture, and for this, I’m grateful for the opportunity to broaden my thinking.

In the Building B of what the now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, I noticed an exhibition introducing current museum activities. There was an exhibition about a Cambodia/Okinawa collaboration project which peaked my interest. It is a program where Okinawa and Cambodia, each having shared war experience on their soil, worked together to create museums that would generate a ‘peace culture’ based on the painful lessons learnt from their past. Through the project, seven members of the museum staff were trained for a month in Okinawa in all aspects of museum management. After returning to Cambodia, they utilized their training efforts in drafting action plans for the long-term management of Cambodia’s museum artifacts. The project started in 2012 and concluded in 2014. Although I live in Okinawa, I had no idea about this initiative and it and came as a surprise because I never expected that Cambodia would have a connection with my home.

During the program I learnt about two distinctive perspectives on peace that I hadn’t considered before. One is ‘negative peace’ that is the absence of war or armed conflict. The other one is ‘positive peace’ that is the presence of social justice and equality, and the absence of structural or indirect violence. For Cambodia, given its turbulent history, the country has been on the track of improvement in recent years. It is obviously peaceful when compared to the past, but still there are many obstacles such as hunger, levels of education, public health, gender equality, child mortality and so on. There is no war now but other threats still remain for the people of Cambodia.

Cambodia’s educational system offers examples of some of the issues that are yet to be resolved as the country develops. The Education network was torn apart during the Khmer Rouge regime, and when order returned, the education system was reconstructed from almost nothing in the 1980s and 90s. But there is still much to do. Although primary school enrolment is around 90%, the dropout rate is high. Half of the students who enter primary school fail to finish. Financial challenges and the need to become breadwinners lead to dwindling student enrolment, and when this takes place the opportunity to learn precious life skills passes by. Apart from on the academic side, missing school can also lead to poor social skills and a lack of responsibility in the young. As a result, some of Cambodia’s youths have poor communication skills, develop bad attitudes, and experience a loss of spiritual development.

My time in Cambodia has focused my attention on peace, the ‘real’ meaning of peace, and ‘effective’ peace education. It also pushed me to think more about my own attitudes, my education in Okinawa, and an individual’s personal responsibilities. Although it was unexpected when I arrived in Cambodia, the PASHA short program left me thinking as much about peace as an Okinawan, for my home prefecture, and for this, I’m grateful for the opportunity to broaden my thinking.

It is estimated that 14,000 to 20,000 prisoners perished while held at S-21, only eight survived.

Cambodia’s ‘Can-Do’ Attitude

OSIPP, Osaka University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

Before arriving in Cambodia, my image of the country was that it was mired in poverty and insurmountable challenges. I was misguided in this thinking. Joining the program totally changed my views and my overall impression now is one of positivity and hope.

There were several lectures highlighting the challenges that Cambodia needs to overcome and the action that is taking place. These are things like developing the economy, alleviating poverty, and dealing with gender issues and security. We all learned a lot from these sessions and felt positive that Cambodia is on the right track in its efforts.

We saw for ourselves an example of hope when on the second day we visited the Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate (FLOW). They accept children from 6 to 11 years old; at present, they are looking after around 300 children. The residents are learning the skills necessary to lift themselves out of poverty and to make a better life for themselves. They learn many life skills and FLOW also has an extensive library where children can hone their reading and writing skills and even undergo English language training.

Most impressively, FLOW doesn’t turn it back on those when they reach 18 years old and support is still offered to help them fully integrate in society. Most of the children find gainful employment because of the skills and values instilled at FLOW. A good number of children also go on to benefit from university education. So far, FLOW has seen 79 of its children graduate from university and then proceed with their own lives. At present, 37 of its children are attending university courses and this is supported by FLOW. Mr. Nuon So Thero, the director of FLOW said that they continue to support those who are older than 18 because if they leave them to fend by themselves, then they may struggle to integrate in society once moving from an institutionalized environment. During our time at FLOW I felt the power of the young people, they were studying hard to get a good job and contribute to society. The same ‘can-do’ attitude can be found everywhere in the country. The students of Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC) are serious students; their passion to make better lives for themselves is real.

Cambodia still faces many challenges in the days ahead. Things are changing quickly, but as the economy picks up steam, so too does the gulf between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots.’ Polarization is stark; slums are widespread, and human trafficking commonplace. The PUC students said the huge gap between the rich and the poor exacerbates trafficking issues. As the immigration issue is one of research areas, it was very interesting to hear the views of PUC students.

Despite the issues that Cambodia still face, there’s still a feeling that the spirit of its people will eventually win through. This ‘can-do’ attitude is very real, and despite the hardships and difficulties that are still to be faced, there is positivity and hope all around … I was happy to return to Japan with a more positive image than when I arrived.

I will never forget of what I learn and felt in Cambodia and would like to thank the PAHSA organizers for giving me the chance to experience so many different things.

There were several lectures highlighting the challenges that Cambodia needs to overcome and the action that is taking place. These are things like developing the economy, alleviating poverty, and dealing with gender issues and security. We all learned a lot from these sessions and felt positive that Cambodia is on the right track in its efforts.

We saw for ourselves an example of hope when on the second day we visited the Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate (FLOW). They accept children from 6 to 11 years old; at present, they are looking after around 300 children. The residents are learning the skills necessary to lift themselves out of poverty and to make a better life for themselves. They learn many life skills and FLOW also has an extensive library where children can hone their reading and writing skills and even undergo English language training.

Most impressively, FLOW doesn’t turn it back on those when they reach 18 years old and support is still offered to help them fully integrate in society. Most of the children find gainful employment because of the skills and values instilled at FLOW. A good number of children also go on to benefit from university education. So far, FLOW has seen 79 of its children graduate from university and then proceed with their own lives. At present, 37 of its children are attending university courses and this is supported by FLOW. Mr. Nuon So Thero, the director of FLOW said that they continue to support those who are older than 18 because if they leave them to fend by themselves, then they may struggle to integrate in society once moving from an institutionalized environment. During our time at FLOW I felt the power of the young people, they were studying hard to get a good job and contribute to society. The same ‘can-do’ attitude can be found everywhere in the country. The students of Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC) are serious students; their passion to make better lives for themselves is real.

Cambodia still faces many challenges in the days ahead. Things are changing quickly, but as the economy picks up steam, so too does the gulf between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots.’ Polarization is stark; slums are widespread, and human trafficking commonplace. The PUC students said the huge gap between the rich and the poor exacerbates trafficking issues. As the immigration issue is one of research areas, it was very interesting to hear the views of PUC students.

Despite the issues that Cambodia still face, there’s still a feeling that the spirit of its people will eventually win through. This ‘can-do’ attitude is very real, and despite the hardships and difficulties that are still to be faced, there is positivity and hope all around … I was happy to return to Japan with a more positive image than when I arrived.

I will never forget of what I learn and felt in Cambodia and would like to thank the PAHSA organizers for giving me the chance to experience so many different things.

The field trip on the second day to Future Light Orphanage of Worldmate. Two of the orphans pose with the students and professor.

Hope

IDEC, Hiroshima University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

This was my third trip to Cambodia although it was my first time in the country while on a study program. I was an undergraduate and knew absolutely nothing about Cambodia on my first visit; my only purpose was sightseeing – such as visiting Angkor Wat. But my tour also included Cambodian culture and history and I was able to start to build a fuller picture about the country. Learning about development in Cambodia is very meaningful, especially for those like me who come from developed countries. It is important for us to learn and discover by actually experiencing, and the PAHSA short program in Cambodia offered the most real experience so far.

On this visit, I was surprised at the massive economic gap in Cambodia. As previous visits were usually to Siem Reap or Battambang, The long stay in Phnom Penh was a real eye-opener. Wealth gaps in rural areas are not so apparent, but in Phnom Penh fantastic wealth and desperate poverty are often juxtaposed. When I broached this subject with local primary school students, many recounted the desperate struggle faced by many families for food and shelter. Surrounding those students were empty desks of schoolmates who had forgone school to earn money to survive.

The same students were interested in how Japan had rebuilt after the war. Even though I’m not an economist, I could speak about the Japanese heart and never-say-die attitude, things I had seen for myself. My hometown, Nagasaki, was devastated by the Atomic Bomb but we managed to rebuild. As soon as trees started to re-bud, there was a glimmer of hope and people picked themselves up. Similarly, the same spirit was seen when the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, people could find hope somehow too. I saw some of the same spirit in the young students that I spoke to in the school. I left them feeling positive about their future despite the hurdles that they still have yet to overcome.

This, my third trip to Cambodia, was by far the most meaningful. Thanks to the program at Pannasastra University of Cambodia, we sat alongside local students and were able to find out about the issues closest to their hearts. I will return to Cambodia next year in order to do fieldwork. But I will also speak to more young people, and I urge other Japanese students to build connections too. The opportunity to do this is one of the greatest things about the PAHSA program.

On this visit, I was surprised at the massive economic gap in Cambodia. As previous visits were usually to Siem Reap or Battambang, The long stay in Phnom Penh was a real eye-opener. Wealth gaps in rural areas are not so apparent, but in Phnom Penh fantastic wealth and desperate poverty are often juxtaposed. When I broached this subject with local primary school students, many recounted the desperate struggle faced by many families for food and shelter. Surrounding those students were empty desks of schoolmates who had forgone school to earn money to survive.

The same students were interested in how Japan had rebuilt after the war. Even though I’m not an economist, I could speak about the Japanese heart and never-say-die attitude, things I had seen for myself. My hometown, Nagasaki, was devastated by the Atomic Bomb but we managed to rebuild. As soon as trees started to re-bud, there was a glimmer of hope and people picked themselves up. Similarly, the same spirit was seen when the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, people could find hope somehow too. I saw some of the same spirit in the young students that I spoke to in the school. I left them feeling positive about their future despite the hurdles that they still have yet to overcome.

This, my third trip to Cambodia, was by far the most meaningful. Thanks to the program at Pannasastra University of Cambodia, we sat alongside local students and were able to find out about the issues closest to their hearts. I will return to Cambodia next year in order to do fieldwork. But I will also speak to more young people, and I urge other Japanese students to build connections too. The opportunity to do this is one of the greatest things about the PAHSA program.

Local Cambodian students and their PAHSA visitors studied alongside each over.

Past … Present … Future

IDEC, Hiroshima University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

Like other students on the PAHSA short program in Cambodia, perhaps by far the most troubling part of the program was the visit to Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Death is everywhere, the building is a monument to inhumanity and the visit was deeply unsettling.

At one time, the building was a happier place however; it was one of the secondary schools in the capital, called Tuol Svay Prey High school. In April 1975, Pol Pot and his clique transformed it into feared prison called ‘S-21’ (Security Office 21) which was the biggest torture center in Democratic Kampuchea.

No doubt, many students have written about their feelings about this place and I’m sure I cannot add anything to their accounts. But on reflection having visited the museum, I am interested in how the Cambodian people understand or view what took place in the past. I’ve been told that that some Cambodians see Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum with such shame that they wouldn’t even visit. This struck me as odd. The Japanese also have dark and terrible periods in history, but my friends and I wish to understand and learn from these. To understand all of our history and reflect on our mistakes is critical if we’re to build a more peaceful world as we move forward.

Perhaps people wish to forget the past because Cambodia is now a country in transition and the economy is improving rapidly. Yet just beneath the gloss of luxury shopping malls and western fast food outlets, the struggle for basic necessities for the most impoverished has seen little upswing. If anything, the greater polarization brings into focus the travesty of hardship that so many suffer in Phnom Penh.

I talked with TukTuk drivers and Hotel employees. One TukTuk driver told me how life was hard and that he had to sleep on his TukTuk every night. On rainy days there are no customers. Most of the drivers come from the provinces to earn money to send and support families. For these people, there’s been little trickle-down from the economic growth. There were similar tales of hardship from the hotel employees I spoke to. One came to Phnom Penh to study tourism at University. His university was a national university and he is now in debt. He said that Cambodia was a poor country and he couldn’t get much money no matter how hard he worked. For these people the impressive economic growth is meaningless, they believe they will never be able to afford to shop in the luxury malls or eat in expensive restaurants. The Cambodian students that we studied alongside told us similar stories.

Certainly, my time in Cambodia on the PAHSA short program has left me with a lot to think about, and as a student, this has to be a good thing.

At one time, the building was a happier place however; it was one of the secondary schools in the capital, called Tuol Svay Prey High school. In April 1975, Pol Pot and his clique transformed it into feared prison called ‘S-21’ (Security Office 21) which was the biggest torture center in Democratic Kampuchea.

No doubt, many students have written about their feelings about this place and I’m sure I cannot add anything to their accounts. But on reflection having visited the museum, I am interested in how the Cambodian people understand or view what took place in the past. I’ve been told that that some Cambodians see Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum with such shame that they wouldn’t even visit. This struck me as odd. The Japanese also have dark and terrible periods in history, but my friends and I wish to understand and learn from these. To understand all of our history and reflect on our mistakes is critical if we’re to build a more peaceful world as we move forward.

Perhaps people wish to forget the past because Cambodia is now a country in transition and the economy is improving rapidly. Yet just beneath the gloss of luxury shopping malls and western fast food outlets, the struggle for basic necessities for the most impoverished has seen little upswing. If anything, the greater polarization brings into focus the travesty of hardship that so many suffer in Phnom Penh.

I talked with TukTuk drivers and Hotel employees. One TukTuk driver told me how life was hard and that he had to sleep on his TukTuk every night. On rainy days there are no customers. Most of the drivers come from the provinces to earn money to send and support families. For these people, there’s been little trickle-down from the economic growth. There were similar tales of hardship from the hotel employees I spoke to. One came to Phnom Penh to study tourism at University. His university was a national university and he is now in debt. He said that Cambodia was a poor country and he couldn’t get much money no matter how hard he worked. For these people the impressive economic growth is meaningless, they believe they will never be able to afford to shop in the luxury malls or eat in expensive restaurants. The Cambodian students that we studied alongside told us similar stories.

Certainly, my time in Cambodia on the PAHSA short program has left me with a lot to think about, and as a student, this has to be a good thing.

TukTuk drivers have hard lives and some sleep on their TukTuks

History Can Be the Best Teacher

OSIPP, Osaka University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

The PAHSA Short Program in Cambodia was eye opening, I had so many new experiences that I would never get in Japan. But without doubt, the events that left the greatest impression were the visit to The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and the lecture by Mrs Emma Leslie. I’m sure many of the other students will write about the museum so I will not cover the same ground here. But I’d like to add a personal anecdote that left a deep impression with me.

When returning to Pannasastra University after visiting Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, I shared with Cambodian students how much I was moved by the tragedy that had played out there. In response I was told that many Cambodians didn’t want to visit the museum. For them, it would mean looking back on the history of the genocide and opening a door to the past. Instead they preferred just to move on and leave the tragic events to history. Of course I fully understand such traumatic emotion, and yet history can be the best teacher, especially when it so graphically documents other people’s mistakes. At the museum in the middle of the yard, there is a monument that says, “Nous n’oublions jamais les crimes commis sous le regime du Kampuchéa démocratique” which translated means, “We never forget the crimes committed under the Kampuchea democratic regime.” The sentiment should never be forgotten, no matter how unpalatable or the discomfort of the reality of the place. The message is true for Cambodians but also for the world.

At one of the lectures at Pannasastra University, Mrs Emma Leslie spoke about reconciliation as a concept. She is Executive Director of the Centre of Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS). The CPCS has an office in Siem Reap City, Cambodia, and it works to further strengthen, support and share Asian approaches to conflict transformation. According to the CPCS, these are undertakings that aim to contribute to peacebuilding efforts in the region with the overall goal of enhancing the sustainability and efficiency of peace work.

Mrs Leslie’s lecture started by reviewing the history of religion in Cambodia. By looking back on the history of religious changes in Cambodia, we could understand the root cause of the problem of fixed social class. Also, after the lecture, the role of religion in the Khmer Rouge tragedy became clearer for me. Religion was linked to a great deal of tragedy under the regime, all faiths were outlawed and any person seen taking part in religious rituals or services was executed. Several thousand Buddhists, Muslims, and Christians were killed for exercising their beliefs. Family relationships not sanctioned by the state were also banned.

The lecture also examined reconciliation, specifically three types; political reconciliation, international reconciliation and cultural reconciliation. I was very interested in cultural reconciliation as it is more personal for so many people given the importance of drawing a line under the past and moving forward in their lives. This type of reconciliation is critical for society to heal.

Now back in Japan it enables time to reflect. I realize that the experience in Cambodia will strongly motivate me to continue my research about peace building and conflict resolution issues.

When returning to Pannasastra University after visiting Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, I shared with Cambodian students how much I was moved by the tragedy that had played out there. In response I was told that many Cambodians didn’t want to visit the museum. For them, it would mean looking back on the history of the genocide and opening a door to the past. Instead they preferred just to move on and leave the tragic events to history. Of course I fully understand such traumatic emotion, and yet history can be the best teacher, especially when it so graphically documents other people’s mistakes. At the museum in the middle of the yard, there is a monument that says, “Nous n’oublions jamais les crimes commis sous le regime du Kampuchéa démocratique” which translated means, “We never forget the crimes committed under the Kampuchea democratic regime.” The sentiment should never be forgotten, no matter how unpalatable or the discomfort of the reality of the place. The message is true for Cambodians but also for the world.

At one of the lectures at Pannasastra University, Mrs Emma Leslie spoke about reconciliation as a concept. She is Executive Director of the Centre of Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS). The CPCS has an office in Siem Reap City, Cambodia, and it works to further strengthen, support and share Asian approaches to conflict transformation. According to the CPCS, these are undertakings that aim to contribute to peacebuilding efforts in the region with the overall goal of enhancing the sustainability and efficiency of peace work.

Mrs Leslie’s lecture started by reviewing the history of religion in Cambodia. By looking back on the history of religious changes in Cambodia, we could understand the root cause of the problem of fixed social class. Also, after the lecture, the role of religion in the Khmer Rouge tragedy became clearer for me. Religion was linked to a great deal of tragedy under the regime, all faiths were outlawed and any person seen taking part in religious rituals or services was executed. Several thousand Buddhists, Muslims, and Christians were killed for exercising their beliefs. Family relationships not sanctioned by the state were also banned.

The lecture also examined reconciliation, specifically three types; political reconciliation, international reconciliation and cultural reconciliation. I was very interested in cultural reconciliation as it is more personal for so many people given the importance of drawing a line under the past and moving forward in their lives. This type of reconciliation is critical for society to heal.

Now back in Japan it enables time to reflect. I realize that the experience in Cambodia will strongly motivate me to continue my research about peace building and conflict resolution issues.

Mrs Emma Leslie, Executive Director of the Centre of Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS)

Inspiration

OSIPP, Osaka University

@ Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC)

As this is the last essay from those that attended the PAHSA Short Program in Cambodia, following the excellence of the other essays, I would hope not to repeat too much about the major events that took place during our time there. Instead I’d like to share a story about personal connections. It is about people with hope.

It is true that Cambodia is still traumatized by its history, and yet the warm welcome we felt on arrival from the students in Phnom Penh was genuine and heartwarming. Recalling Prof. Trond Gilberg, the Dean of Faculty of Social Science, PUC, he said:

It is true that Cambodia is still traumatized by its history, and yet the warm welcome we felt on arrival from the students in Phnom Penh was genuine and heartwarming. Recalling Prof. Trond Gilberg, the Dean of Faculty of Social Science, PUC, he said:

As you can see, Phnom Penh today is not the same as Phnom Penh ten years ago. All has vastly developed. I would like to emphasize that this better Cambodia is thanks to the young generation who led the change.”

In his introductory lecture, the role of youth in the development of Cambodia was a theme that Prof. Gilberg often returned to.

We don’t need to look far to see the difference that young people are making, like last year when the parliamentary elections were held. The young generation stood up and demanded that their voice be heard; the move for the betterment of Cambodia was palpable and couldn’t be ignored by the entrenched politicians. As long as the youth stand as agents of change, it could only bring light to Cambodia’s development and sustained peace. Here are some interesting stories of inspiration from young Cambodians.

We don’t need to look far to see the difference that young people are making, like last year when the parliamentary elections were held. The young generation stood up and demanded that their voice be heard; the move for the betterment of Cambodia was palpable and couldn’t be ignored by the entrenched politicians. As long as the youth stand as agents of change, it could only bring light to Cambodia’s development and sustained peace. Here are some interesting stories of inspiration from young Cambodians.

In the photo above, I am with Sokla, a PUC student whom I call Eun Sokla which means Brother Sokla; this expresses how close we became. On the field trip I’d ask Sokla questions. At one point when I saw the horrors of the Khmer Rough on display before me, I asked how this tragedy could have happened and how people faced such horrors? Sokla answered:

We also ask why this conflict happened and why we had to burden this loss. But we cannot blame anyone. The culprits may be are our parents, our family, our friends, and our neighbors. If we try to continually blame and investigate, should we really be living like that? Of course it was a tragedy, we all feel that the loss was inhumane. But we should move on, not trapped in the past memory but think about now, how we should step forward. Move past the horrors and shape a better future. A cruel sea can make great sailors.

The magnanimity of Sokla’s statement touched me deeply. And looking around Phnom Penh I could only concur wholeheartedly.

On another occasion, while visiting peripheral areas around Phnom Penh I met a boy, a flower seller around the Tonle Bati temple. When taking photos of the temple he approached me to try for a sale. Slightly confused, I asked him why I should to buy flowers. He replied:

On another occasion, while visiting peripheral areas around Phnom Penh I met a boy, a flower seller around the Tonle Bati temple. When taking photos of the temple he approached me to try for a sale. Slightly confused, I asked him why I should to buy flowers. He replied:

Sir, this flower for praying to the God but since you are a tourist, you do not need to do this. However sir, would you buy this to me? I need money to pay my education. I am so poor but I hardly sell this to pay my education fee. I do not wish to be a poor and I do not want to be a beggar therefore I believe school is only option for escape from this condition.

Again, there was little I could say to this. He spoke to me in English and seemed to value the importance of formal learning. On a similar theme, another PUC student, Soksan, talked about the struggles to find better lives through education.

My life has not been easy, I was born in a rural area outside Phnom Penh with unfortunate economic hardship. I went to the city hoping to get educated. But I must admit my journey was tough. I needed money to pay tuition fees and had to work hard for it. I suspended my university entrance to work and save for the school fees. I had to do many jobs even after university entrance. Studying and working day-and-night is difficult. The price I paid was my health. I survived only on a couple of hours of sleep a day. My family couldn’t understand this. They said I could work at the village as a farmer but I wanted more than that. Education would open the door to escape from poverty, broaden my knowledge and see the world.

Fortunately, things worked out well. Soksan thrived in his university life and even saw a little of the world when he traveled to Japan for the PAHSA Short Program in Hiroshima.

If I was to sum up my feeling after the short program in Cambodia, I could do this in one word, ‘inspiration.’ The sharing of first-hand moral and life lessons can only inspire. The sheer tenacity from the youth to become educated, improve their lives, and along the way fix society in economic and social terms, can only help me focus as my own study journey ahead. Their stories will be my inspiration to study harder and to try to inspire others in the future the same way that I’ve been inspired here in Cambodia.

If I was to sum up my feeling after the short program in Cambodia, I could do this in one word, ‘inspiration.’ The sharing of first-hand moral and life lessons can only inspire. The sheer tenacity from the youth to become educated, improve their lives, and along the way fix society in economic and social terms, can only help me focus as my own study journey ahead. Their stories will be my inspiration to study harder and to try to inspire others in the future the same way that I’ve been inspired here in Cambodia.

PHOTOS

PAHSA is part of "Campus Asia." Supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan

Download the PAHSA Brochure

PAHSA sister sites

.gif)